Join me on my new blog: http://fathermarkcollins.blogspot.com!

This is my final post here!

18 October 2008

06 June 2008

News

Been a while since I posted here, but things continue apace. Of note:

I signed a letter of agreement with the Rev. L. Kathleen Liles and, in August, I will become the Assistant to the Rector at Christ & St. Stephen's Church in Manhattan. I'm very pleased to be joining Mother Liles in ministry and to be called to serve the people of this wonderful parish.

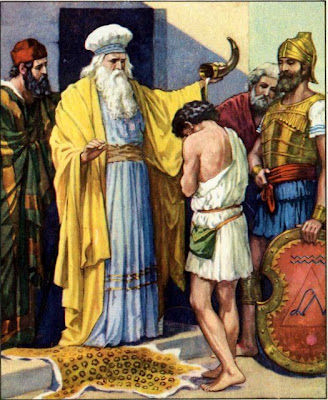

The Ordination of St. Stephen by Vittore Carpaccio

It was expected, but nonetheless, is good to hear that the Standing Committee of the Episcopal Diocese of New York has approved my ordination to the priesthood. That long-awaited event will take place on Saturday, September 20th at 10:30am in the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine here in Manhattan. There will be a reception that afternoon at Christ & St. Stephen's. And I will preside at Holy Eucharist for the first time the next day, Sunday, September 21st, also at Christ & St. Stephen's.

In the interim months before I begin at CSS, I'm working for Episcopal Charities of the Diocese of New York; which means I'm working on the Cathedral Close everyday and get to see things like my bishop waiting for the crosstown bus. Right now we're raising money for feeding programs in Episcopal parishes across the diocese.

In the interim months before I begin at CSS, I'm working for Episcopal Charities of the Diocese of New York; which means I'm working on the Cathedral Close everyday and get to see things like my bishop waiting for the crosstown bus. Right now we're raising money for feeding programs in Episcopal parishes across the diocese.

Click here to donate to these and other EC sponsored programs.

That's all for now. Watch this space for much jubilation when we find a place to live!

15 May 2008

The Cross of Love

I was on retreat several years ago, very early in the discernment process that would eventually lead me here to General Seminary. Several of us had gathered at a monastic outpost for a five day silent retreat. We were not a group, just individuals who for our various reasons, had come to seek silence and prayer in the woods of northern Massachusetts.

The silence was to begin after Compline, so our first evening meal was a speaking meal. I learned that one of the retreatants at my table was heading back to seminary after a course in clinical pastoral education. She told us how, on the first day of the course at a hospital in Boston, the nun who was to be their supervisor had asked the incoming CPE class why they were there. A variety of answers were given: To be of support to the sick, to learn how best to comfort those in need of comfort, to help people -- my bishop made me do it! As they spoke, the incoming students began to notice that each reason seemed to garner a somewhat qualified acceptance from the good sister. The students begin to sense that there was a right answer as to why they were there, and that none of them had yet given it. Finally, their supervisor looked these new chaplains in the eye and told them the truth which perhaps none of them had yet come to know.

She leveled her gaze upon them and told them, “You are here, every one of you, because you are wounded. Each of you, in some way, bears a wound in your heart and soul. It may be a childhood wound, or a spiritual wound or a long healed physical wound, but you each have one. And God has called you out of that woundedness, to be with others in their woundedness, and to show forth God’s healing love.”

Some few years ago, many of us took up everything we owned, our loved ones, and the good wishes of our parishes and dioceses, to follow the call of Christ -- and to come here to General Seminary; to this Close, to this Chapel, to this altar. We came with tremendous hopes and great faith. We brought all our life experience, be it long or short. We brought all our gifts and over three years I have come to know that among us there are myriad gifts, gifts of creativity, and inspiration, gifts of music and song, gifts of leadership (like when Arianne tells me what to do) and gifts of followership (like when I do what Arianne tells me to do!), gifts of tenacity, gifts of humor, gifts of compassion and understanding.

Some few years ago, many of us took up everything we owned, our loved ones, and the good wishes of our parishes and dioceses, to follow the call of Christ -- and to come here to General Seminary; to this Close, to this Chapel, to this altar. We came with tremendous hopes and great faith. We brought all our life experience, be it long or short. We brought all our gifts and over three years I have come to know that among us there are myriad gifts, gifts of creativity, and inspiration, gifts of music and song, gifts of leadership (like when Arianne tells me what to do) and gifts of followership (like when I do what Arianne tells me to do!), gifts of tenacity, gifts of humor, gifts of compassion and understanding.And we took up our own woundedness as well. We brought our shadow sides with us to seminary. We came with our egos and jealousies and pettiness. We came with our narrowness of mind. We came with our past hurts and our ability to cause hurt. We are the survivors of dysfunctional families, we are the sometimes broken hearted and the oft lame of spirit. We are all of us flawed, all of us wounded, and we are all of us in great, great need of God’s grace.

All of our great gifts -- and all of wounds came with us here to General. Each of us have taken up our cross, and brought it to this place, planted it firmly in the soil of this Close, and we have done so in order to do what God has called us to do -- to follow Christ.

And now, as our epistle says, the end of all things is near. We are poised to move from this seminary into the outside world. We go out of this place with much learning, more experience, but also with the realization that we can’t and won’t cure all the world’s ills, or all the church’s ills, and knowing that the healing that we offer is bounded by the properties of God’s creation.

So, what is it we will offer the church? What can we, as gifted yet flawed followers of Christ, do for the people that we are being sent to serve?

We can love them.

Our epistle today tells us to maintain constant love for one another, that love covers a multitude of sins. To love those we are called to serve in ministry is the one thing we can do that calls upon both our giftedness and our woundedness. It is through our own pain that we can truly see and feel the pain of others. It is in recognition of our own brokenness that we can come to love the brokenness of others. In loving, we serve our God wholly, because it is in loving we deny our false selves, and we bring to bear all sides of our true selves, our full humanity, the same humanity that was sanctified by God in our creation, in the Incarnation, and by our baptism.

In loving the children of God entrusted to us in ministry, and loving them out of our own life’s pain, our wounds are redeemed, and become the means of a further Incarnation, a conduit through which more of God’s love enters the world.

Love covers a multitude of sins, and sins are something we are sure to encounter and sure to commit on our journeys. Whether as lay or ordained ministers, our vocations will bring us into contact with our own sinfulness, and with the sinfulness and brokenness that are always part of Christian community.

I have some bad news: I don’t know how to tell you this, but: The church is not a hot-bed of mental and emotional health. Parishes and church institutions are where very many people bring their giftedness, yes, but also their hurts and fears, their narcissism and passive-aggression, their grief, their loneliness, and their pride -- and then there are the parishioners themselves!

In our ministries, I know that we will meet all manner and type of God’s children: And through it all, I think there is only one thing that we must always do -- and that is to love those God has called us to serve.

The medieval mystic Julian of Norwich tells us that Love is without beginning, is and shall be without ending; that God wills that we be like God in wholeness of love to ourselves and to our even-Christians, our brothers and sisters in Christ.

The medieval mystic Julian of Norwich tells us that Love is without beginning, is and shall be without ending; that God wills that we be like God in wholeness of love to ourselves and to our even-Christians, our brothers and sisters in Christ.We go out from this place to preach and to teach and to participate in the sacraments, we are to form children in the faith, we are to work for justice, we will celebrate baptisms, deaths, marriages, conversions. We will preside over vestry meetings, and meet with committees. We will anoint the newborn and the dying; we will weep with the sorrowful and shout in celebration with the joyous. We will do many things, and undertake many tasks, and do all manner of good to the glory of God. And we will fail in many things; we will be humbled, and on some days, I expect, be brought quite low. We will be admired, despised, beatified and vilified. And I don’t think that much of that matters, in the end.

I think that the only thing we must do, and must do in every situation is love.

We have taken up our crosses to come to this place, and take them up again we must as we leave. Our own crosses, our own woundedness, our burdens and shortcomings and our own pain will be crucial to our ministering to the woundedness and pain of others and to our witness to a broken, wounded world. Our many talents and gifts and our learning will serve us well, that is most certainly true. But it is the wounds we bear that will serve us most when we seek to comfort the wounded, when we attempt to bring healing to a broken world.

So, we take up our own crosses now to follow Christ even further and in so doing we take up the Cross of Christ as well; the cross on which Jesus was wounded, the cross by which the whole world was redeemed. For can there be, was there ever, a greater icon of unending love than the cross upon which Christ offered himself as a most loving sacrifice. The cross of Christ is the unequivocal evidence of the endless, unconditional love that God bears for all humanity.

So, we take up our own crosses now to follow Christ even further and in so doing we take up the Cross of Christ as well; the cross on which Jesus was wounded, the cross by which the whole world was redeemed. For can there be, was there ever, a greater icon of unending love than the cross upon which Christ offered himself as a most loving sacrifice. The cross of Christ is the unequivocal evidence of the endless, unconditional love that God bears for all humanity.Of God’s grace, Jesus was given for us, to be human, to share our life, to give himself for us, a holy and fragrant offering. All that was done for us: the cross, the tomb, the resurrection and ascension was done for love.

Many years after her first mystical experiences, Julian of Norwich was again visited with visions. She wrote, “From that time… I desired oftentimes to learn what was our Lord’s meaning. And fifteen years after, I was answered in ghostly understanding, saying thus: Wouldst thou learn thy Lord’s meaning in this thing? Learn it well: Love was His meaning. Who shewed it thee? Love. What shewed He thee? Love. Wherefore shewed it He? For Love. Thus was I learned that our Lord’s meaning was Love.”

We have come, bearing our crosses, to this place to be fed, to be formed, to be fortified in faith, and to be sent forth. Later today we cross that Chapel step that reads “through the gates and into the city” and today, we will take those words literally, and go out from this place to serve God’s people in God’s holy church. We won’t go out like the disciples, two by two, but single file (or we will if we were paying attention at rehearsal yesterday!) We won’t be carrying staffs, but we will be wearing some cool new academic hoods. We won’t be in sandals I don’t guess, but I know that whatever shoes Julie wears will be red!

We go from this place, having again taken up our crosses and with them the cross of Christ. And as we go, we lift high that cross, so that the love of Christ may be proclaimed wherever we go, in whatever we do for the people that God calls us to love and to serve.

Yes, the end of all things is near. And as Julian proclaimed, in the end all shall be love.

~ Amen.

© The Rev. Deacon Mark R. Collins

11 May 2008

Farewell to St. James, Fordham Manor, the Bronx

Today, May 11th -- Mother's Day and Pentecost -- was my last Sunday as seminarian at St. James Fordham in the Bronx. St. James has been my spiritual home for two years. Fr. Tobias Haller, Br. James Teets, Ms. Monica Stewart, Mr. George Green, and so many others have been my mentors and teachers, and friends. This morning for Pentecost we sang "There's a Sweet, Sweet Spirit in this place..." I can testify to that!

08 May 2008

The Alumni/ae Prize in Ecclesiastical History

It's a bit naff to do this, but this blog is serving as an online resume for me these days, so here goes...

It's a bit naff to do this, but this blog is serving as an online resume for me these days, so here goes...

I'm proud to let you all know that I've been awarded the Alumni/ae Prize in Ecclesiastical History for 2008. The award was established in 1895 for the graduating student essay on "the historical interpretation of the life and thought of the Church of England with special reference to its continuity with the ancient Catholic church". In this case, 'Church of England' is broadly extended to include The Episcopal Church and the Anglican Communion. We were given a choice of three quotes to base our essay on. The essay had to be written in a two-hour period, and was 'open book'. I'm not saying this essay is my best work, but as the last thing written in my senior year, at the end of exam week, and at the tail end of three tedious but thrilling years of study, it ain't so bad. My essay text is below:

“This is and has been the open profession of the Church of England: to defend and maintain no other Church, faith, and religion than that which that is truly Catholic and Apostolic and for such warranted, not only by the written word of God but by the testimony of the Ancient, Godly Fathers.”

—John Overall, Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral, London

John Overall was born in 1559, months after Elizabeth I had come to throne and in the year that the Book of Common Prayer was reestablished as the standard of faith for the Church of England. Overall was a translator of the Authorized Version of the Bible under James I & VI. Overall’s defense of the Church of England in this short statement hinges on three assertions of the Church of England’s identity. It is Catholic and Apostolic, it is Biblical, and loyal to the interpretations of the faith of the earliest Church Fathers. This Church of England is then a catholic church in that in addition to the Bible, it follows those catholic principles of fealty to the earliest Christian church which professed a faith believed to be handed down directly from the apostles and formed by the early church fathers.

Overall’s defense is notable for what it omits. It omits the authority of the Pope. It omits the authority of church councils later than Chalecedon, notably the Council of Trent, while including those councils where the creedal statements of the faith were compiled (i.e. the testimony of the Ancient, Godly Fathers). It omits such later philosophies and theologies that may have become accepted by the church such as the work of Thomas Aquinas. Overall’s assertion is that the Church of England is catholic in that it is authentic to the earliest examples of Christianity and to Christian scripture.

The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church gives this definition of the term catholic as meaning, “In general, in present-day usage, it is employed of those Christians who claim to be in possession of a historical and continuous tradition of faith and practice, as opposed to Protestants, who tend to find their ultimate standards in the Bible as interpreted on the principles of the Reformation of the 16th century” (305-6). We see in Overall’s statement that not only is he omitting certain ideas about catholicity that would have been claimed by the Roman church, he is also including certain attributes that would have been condemned by the more radical reformers of the 16th century. Overall asserts that the apostolic faith as interpreted by the church fathers is essential to the Church of England. These church fathers and their writings were supercilious to the more radical, Protestant reformers who sought to make scripture alone the standard of Christian religion. For Overall, the Bible is indeed a standard of the faith, but in conjunction with the received apostolic tradition, and the earliest interpretations from the church fathers. It’s worth noting that in including the Bible in his statement Overall uses it in a negative locution: “not only by the written word of God” (emphasis added). Overall deemphasizes the Bible in favor of apostolic tradition, and early church interpretation; a stance somewhat surprising for one of the English Bible’s translators.

In her volume on the early church in The New Church’s Teaching Series, Rebecca Lyman describes the emphases of the English Reformation. “In their search for a catholic and reformed church independent of Rome at the Reformation, Anglicans went back not only to scripture, but to these earliest centuries of the church. Here the reformers found a model for liturgy in the language of the people, a learned and pastoral theology, and the shared authority of the councils” (3). Lyman sees in the newly independent Church of England a clear desire to emulate those earliest Christians from the era when the church was truly catholic and apostolic. Lyman describes the ‘apostolic tradition’ as “the teachings of Jesus that were preached through the earliest missionaries or apostles” (5). She goes on to describe what apostolic and catholic meant in the early church era. “Early Christians used the terms ‘apostolic’ and ‘catholic’ to refer to this core inheritance of the first communities. They defined as authentic and therefore ‘apostolic’ those inherited teachings that could be tested by universal (‘catholic’) and public testimony” (5).

Overall’s immediate ecclesiastical predecessors working in the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and Elizabeth I would have relied heavily on Renaissance humanist scholarship that revered the earliest manuscripts then available. “Those responsible for shaping the Reformation in England… enthusiastically built upon one of the great gifts of the Renaissance, a high regard for the past” (Thompsett 6). Humanist reinterpretation of ancient manuscripts led to new understandings of the earliest Christian communities and their practices. As John Booty writes in his introduction to An Apology of the Church of England by John Jewel, the English reformers saw “humanist studies breaking through the arid and corrupt accumulations of the recent past, providing… the opportunity and the means for probing into the period of the primitive church” (xviii). The English Reformation took advantage of new thought and new learning in order to reach beyond the accretions of medievalism to find a more authentic catholicism in the earliest apostolic church. And it was to this model that they sought to adhere.

“(T)he recovery of ancient Christianity through the work of educated men such as Archbishop Thomas Cranmer significantly affected the polity, spirituality, and worship of the English church in the 16th century. Like others of their day, these reforming scholars saw the ancient church as an authority to cleanse and correct the contemporary church, as well as to deflect Roman Catholicism’s exclusive claims to antiquity and truth” (Lyman 8). Catholicity as understood by Overall and the English reformers was a concept inextricably tied to the early church, and not to the See of Rome. Scholarship had shown a church that was more counciliar, more pure, less corrupted by centralized power, with a great regard for the scriptures. This early church was understood as catholic and it is this catholicity that the Church of England sought to emulate at the Reformation. “In essence, our illustrious Reformation ancestors backed up one thousand years to the traditions of their forebears” (Thompsett 7) in order to find a true religion with which to reform the Church of England. Simply put, the Church of England believed itself to be “offering a more authentic Catholicism than that offered by the Church of Rome” (MacCulloch 493).

The regard for the historically catholic can be found in later eras of Anglicanism. “(T)he ancient church had its most powerful effect on Anglicanism… in the Oxford Movement” (Lyman 11). In an attempt to revitalize the worship and theology of the Church of England, Newman, Pusey, Keble, J. M. Neale and others associated with the Oxford and Cambridge movements sought to revive ancient catholic ecclesiology and ritual. Initially theological, the Oxford Movement was specifically and unashamedly catholic, and sought to move the Church of England away from its more Protestant understanding of polity initially, and later toward more ancient, catholic forms of worship. Anglicanism became more and more ‘Anglo-Catholic’ as a result of the Oxford Movement and the work of the ritualists associated with the movement. These efforts gave Anglicanism back an aesthetical catholicity that once again did not require adherence to Roman authority.

Later efforts to reconcile elements in the Church of England that were struggling with modernism resulted in Anglican bishop and scholar Charles Gore’s Lux Mundi. Gore looked to the Reformation to find a model of reform that valued catholicity while allowing for change. He wrote, “It is the glory of the Anglican Church that at the Reformation she repudiated neither the ancient structure of catholicism nor the new and freer movement” (Lyman 12) toward reform. Gore saw value in maintaining catholicity as essential to Anglicanism as it reformed itself, and proposed that such a model should be followed as Anglicanism struggled to encompass modernity.

As various streams of Christianity sought to move closer together in the United States and in England, the catholic identity of the church was again affirmed in the Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral. In ecumenical endeavors, Anglicanism would maintain sacramentality, creedal theology as derived from the early church councils, Biblical authority, and episcopal governance descended from the ancient church and the apostles themselves. A catholic Anglicanism would continue in the apostolic tradition, with the orders of ministry as described by the church fathers, and with the earliest church’s understanding of sacredness in the two sacraments of baptism and the Eucharist.

As Anglicanism grew and comprised more independent provinces, its essential catholicity was maintained. In describing the Anglican Communion in the 2oth century, Archbishop William Temple wrote, “(Anglicanism is) solidly catholic, as in its doctrine, so also in its affirmation of continuity in time and unity through space, expressed by outward obwervances” (Schmidt 259). Also in the 20th century, regard for early church practice is again seen in the liturgical movement's renewal of worship. “Studies of ancient liturgy also underlay the Liturgical Renewal movement of the 20th century which sought to restore many of the theological and liturgical understandings of prayer and the sacraments from the early church” (Lyman 13). Again Anglicanism seeks to reform itself along catholic lines to maintain its attachment to the practice and theology of the earliest Christian church -- when the undivided church could truly be called catholic and apostolic.

“At the end of (the 20th) century… we may be closer to the intentions of our earliest Christian ancestors than we were at the start” (Thompsett 12). Anglicanism retains its catholic identity today, in its worship, in its creedal theology, in its governance and polity. We continue to maintain the catholicism that was seen in the earliest, undivided Christian church. We continue to define a core catholicity as essential to the church’s identity. Overall’s statement could be made today as easily as it was in the immediate wake of the 16th century reformation of Anglicanism. We were then and continue to be ‘Catholic and Apostolic.’

Booty, J. E. An Apology for the Church of England by John Jewel. New York: Church Publishing. 2002.

Cross, F.L. and E.A. Livingston, eds. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. 3rd ed. New York: OUP, 1997.

Lyman, Rebecca. Early Christian Traditions. The New Church’s Teaching Ser. 6. Cambridge, MA: Cowley, 1999.

MacCulloch, Diarmaid. The Reformation: A History. New York: Viking. 2003.

Schmidt, Richard H. Glorious Companions: Five centuries of Anglican spirituality. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2002.

Thompsett, Fredrica Harris. Living With History. The New Church’s Teaching Ser. 5. Cambridge, MA: Cowley, 1999.

03 May 2008

The Bishop of Newark Preaching Prize

I'm very proud and gratified -- and deeply humbled -- to let you know that I have won the Bishop of Newark Preaching Prize here at General Seminary. The prize comes with a small cash stipend, and with the rather daunting responsibility of preaching at the commencement Eucharist on the morning of my graduation from seminary. So, pray that the Spirit enlightens my mind and heart -- and gives me the voice to proclaim God's word on May 14th.

I'm very proud and gratified -- and deeply humbled -- to let you know that I have won the Bishop of Newark Preaching Prize here at General Seminary. The prize comes with a small cash stipend, and with the rather daunting responsibility of preaching at the commencement Eucharist on the morning of my graduation from seminary. So, pray that the Spirit enlightens my mind and heart -- and gives me the voice to proclaim God's word on May 14th.

The sermon I preached for the judges can be found here.

Update: I found out on Sunday that my field ed supervisor and mentor, the Rev. Tobias S. Haller, BSG also won the preaching prize in his senior year here at General. Good tutelage, obviously; and perhaps the heavenly intercession of St. James the Less!

18 April 2008

Stateside!

"The Major" is back home! Safely returned from a year or so in southern Afghanistan, the Major sent an email earlier today to let me know he's at Ft. Riley, KS, his point of embarkation. He should be safely home in Nashville soon.

Thanks to all of you who prayed for his safety. I hope you'll continue to join me in prayers for peace throughout our world:

Almighty God our heavenly Father, guide the nations of the world into the way of justice and truth, and establish among them that peace which is the fruit of righteousness, that they may become the kingdom of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Amen.

15 April 2008

Sermon for Year A, Easter 4: "Holy Listening"

Preached on the fourth Sunday of Easter, April 13, 2008 at St. James Episcopal Church Fordham Manor. Scripture readings this sermon is based on can be found here.

+ In the name of Christ Jesus, Amen. My father’s farm is in the hill country of West Tennessee, where the landscape begins to hint at the existence of the Great Smokey Mountains further eastward. The gentle rolling hills are thickly wooded in most parts, so pasturelands are often separated from one another; and are usually bounded by hills and forests.

My father’s farm is in the hill country of West Tennessee, where the landscape begins to hint at the existence of the Great Smokey Mountains further eastward. The gentle rolling hills are thickly wooded in most parts, so pasturelands are often separated from one another; and are usually bounded by hills and forests.

A significant part of my father’s working day is about ‘going to check on the cows’. He loads a sack of feed into the back of the pick-up truck. Dogs and people pile into the cab of the truck and we drive sometimes a mile or two over gravel roads to get to one of his pastures where his cattle are grazing.

After the gate is safely closed behind us, my father blows the horn of the pick-up three times. Now, after years of driving over rutted gravel roads, the horn on the pick-up truck is woefully out of tune. It gives off more of a bleat, than a honk. But in a few minutes of that out-of-tune bleat, over the hill or through the woods, come my father’s cows.

My father takes out his pocket knife and opens the sack of feed, something called “Ranch Cubes” which are considered quite the bovine delicacy. He tilts the sack over his shoulder and spreads the feed in a line -- about 20 feet long or so -- on the ground. The cows all gather along this makeshift manger, and begin to feed. My dad walks through the group of heifers and calves, counting, checking ears and eyes for infection. He notes the progression of those heifers that will bear calves in a few weeks or a month. And he looks to the health of the nursing mothers, and the development of their young. As he does so, the cows will gently move aside, some will nuzzle his gloved hand, and he’ll scratch their heads were new horns may be coming in.

The cows all gather along this makeshift manger, and begin to feed. My dad walks through the group of heifers and calves, counting, checking ears and eyes for infection. He notes the progression of those heifers that will bear calves in a few weeks or a month. And he looks to the health of the nursing mothers, and the development of their young. As he does so, the cows will gently move aside, some will nuzzle his gloved hand, and he’ll scratch their heads were new horns may be coming in.

His cattle know him; they know his voice, and the off-pitch bleat of his truck horn. They are mistrustful of a stranger; they do not know my voice or my smell. They shy away from me, but under his hand they are calm, and are at peace.

The Gospel of John from which our reading today is taken is not a gospel of calm or of peace. It is a gospel of conflict, and of division. The term “The Jews” appears 70 times in the gospel of John compared to twice in Matthew, and not at all in Mark or Luke. And it is meant to carry the disapproval and condemnation that so grates on our post-Holocaust ears. It is in John’s gospel that Jesus is seen as one with the Father. The gospel begins with the astonishing claim that Jesus of Nazareth is the Word made flesh, a claim that seems to deny the monotheism that was a the defining element of Judaism -- a claim that would have grated on the ears of first century Jews.

And there is a new word in John that appears no where else in the New Testament, and no where else in all of the Jewish literature of the time: aposynagogos. To be cast out, or put out, from the synagogue. Most scholars agree that the Gospel of John is the last of the gospel accounts to be written. It is a biography of Jesus like Matthew, Mark and Luke, but it is also an autobiography of the community that gathered around John, the beloved disciple --that developed along different lines from the Apostolic that grew up around James and Peter in Jerusalem and the churches Paul founded in Corinth, Ephesus, and Galatia and throughout the Roman empire. As an autobiography of a specific community of believers, the Gospel of John gives evidence of the rough and tumble period of early Christianity when there were many churches struggling to be faithful to the teaching of Jesus, in different places and in different ways.

Most scholars agree that the Gospel of John is the last of the gospel accounts to be written. It is a biography of Jesus like Matthew, Mark and Luke, but it is also an autobiography of the community that gathered around John, the beloved disciple --that developed along different lines from the Apostolic that grew up around James and Peter in Jerusalem and the churches Paul founded in Corinth, Ephesus, and Galatia and throughout the Roman empire. As an autobiography of a specific community of believers, the Gospel of John gives evidence of the rough and tumble period of early Christianity when there were many churches struggling to be faithful to the teaching of Jesus, in different places and in different ways.

This John community accepted the membership of Samaritans, as the account of the Woman at the Well tells us. The John community has experienced conflict with the religious establishment -- “The Jews” -- and had been cast out of their houses of worship. The Gospel of John’s very exalted view of Jesus as the Word made flesh that existed before the creation of the world, would have sounded like blasphemy to most Jews and many Jewish Christians in that time.

So this community of the Beloved Disciple is one that is no stranger to conflict. It has been cast out of the synagogues where most Christian initially worshipped. It has accepted the hated Samaritans as fellow believers. It has come to believe that Jesus is son of God, and very God himself.

Our gospel reading today from John comes just after the healing of the man born blind, an event that caused much consternation for the Pharisees and that led the man born blind’s parents to fear being forced aposynagogos, out of the synagogue.

So, when Jesus says in today’s reading that there are those who are thieves and bandits it is the Pharisees and the other religious forces in the community to which he refers, who would drive out the John community for reveling in the revelation of Jesus as God Incarnate and who have doubtlessly caused the John church so much pain.

There is no doubt that we live in times just as contentious as those we hear about in our readings today. These are times of contention in our church, in our communities, and in our nation. We are at war in Iraq and Afghanistan, and there is unrest in Nigeria, Tibet, Columbia. Some of these conflicts are as old as are our national issues around race, they seem never to come to resolution or reconciliation.

What are we to do in situations such as these? Where are we to turn in times of religious conflict like those found in John, or in our reading from Acts this morning where an argument about the different treatment afforded the Hebrew and Greek widows erupts -- and in which Stephen -- the first deacon -- is taken from the synagogue and stoned to death?

Where do we turn in times of different understandings and interpretations of the faith? Who is it that we are supposed to follow? Who do we look to for guidance when war breaks out, and when tempers flare on street corners, in political debates and in parish meeting rooms?

There are often loud and angry voices in situations such as these. Lots of people have lots of opinions. You can find all kinds of opinions on cable news channels and all over the Internet. There can be real confusion, and real difference of opinion. And hearing so many different opinions and so much criticism -- and to hear so few voices calling for understanding and reconciliation -- all this noise can make us fearful, anxious, even angry.

Noisy, confusing times such as these are times that call for a holy listening. Jesus assures us, we will know his voice when we hear it. It is he who will call us by name. It is he who will lead us through the gate to the pastures of peace, and will not cast us aside. Through him, the good shepherd, the gateway to salvation, we will find the word of truth and pastures of calm and of peace.

In times of conflict, sometimes it is not best to add our voices and opinions to the fray, perhaps we are to engage in holy listening for the sound of what our ears and our hearts will tell us is the voice of our Savior calling to us to follow.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I believe in speaking up and speaking out. I think that all too often, we are silent when the truth of our lives -- our own gospel truths -- is exactly what the world needs to hear. And after we’ve said our piece, then we should do our best to hear what our brothers and sisters are saying.

When there is conflict over how we will relate to each other as Anglicans, or how we can better relate to each other as black folks and white folks or how we here at St. James are to be one body of Christ, though we are West Indians and West Africans and African Americans with different faith traditions and customs. We are brothers and sisters in Christ Jesus -- and we are always that, no matter what -- we are many sheep of one flock, with one shepherd whether we are Hellenists or Hebrews, as one body in Christ Jesus, one flock, we need to listen to each other with very great care.

We are brothers and sisters in Christ Jesus -- and we are always that, no matter what -- we are many sheep of one flock, with one shepherd whether we are Hellenists or Hebrews, as one body in Christ Jesus, one flock, we need to listen to each other with very great care.

Because when we listen with the ears of our hearts, we will hear the truth, we will hear the voice of the Savior calling to us, guiding us forward, showing us the path of righteousness and the way of peace.

We may hear our shepherd’s voice in the words of a sermon, or in the stories we share at coffee hour, in the hymns we sing, or the voices of our children reciting the psalms like they did just a few Sundays ago.

We may hear Christ’s voice in the account of the veteran returned from war, in the cries for freedom from the Buddhist monks of Tibet, in the silence of the poor and the oppressed.

We’ll know it’s our Savior’s voice when it calls us to act with mercy and forgiveness, when it calls us to work for justice and for peace, when we are urged to take on new challenges, to be reconciled with our enemies, to live in love with one another to forgive, to love and to serve.

For the one we are seeking to hear is no ordinary shepherd, the King of Love our shepherd is, and it is in love that he seeks us, and on his shoulder gently laid, home, rejoicing he leads us….

+ Amen.

14 April 2008

The Botafumerio at Sant'iago de Compostela

In the historic church of St. James in Compostela, Spain -the terminal shrine of one of the most important medieval pilgrimage routes - they like a little incense with their worship!

05 April 2008

ETRB VI: "The Altar Steps" by Compton Mackenzie

The Altar Steps by Compton Mackenzie

The Altar Steps by Compton Mackenzie

One of the joys of auditing a course means that you can head down ‘rabbit holes’ in the assigned reading when they attract your attention, and not have to worry about it. In doing some reading for my Modern Anglican Development class, I came across an article originally published in Victorian Studies on Anglo-Catholicism and homosexuality by David Hilliard. The article made reference to Sir Compton Mackenzie’s Anglo-Catholic trilogy of novels. Down the rabbit hole I went.

Mackenzie is most noted for his comic novels of the 1940s Monarch of the Glen and Whiskey Galore set in Scotland. However, earlier in his career, he was seen as a literary novelist and was greatly admired by F. Scott Fitzgerald. Mackenzie was admird for, among other works, his coming of age Sinister Street novel (in 2 volumes), which were compared to W. Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage. Mackenzie’s Anglo-Catholic trilogy of novels -- The Altar Steps, The Parson’s Progress and Heaven’s Ladder -- are another bildungsroman flavored effort on Mackenzie’s part. The main character Mark Lidderdale is, like Mackenzie, deeply religious. And his development as a burgeoning catholic is charted by the three novels. I found a free online copy of The Altar Steps, downloaded it, printed it out and red it through. In the opening chapters of the book, it is the late 19th century and Mark’s father James, an Anglican priest, has come to St. Simon’s Notting Hill, an outpost of the Catholic Movement in the Church of England. Fr. Lidderdale is given charge of the St. Simon’s Lima Street Mission. The Lima Street Mission typifies the outreach to working class and poor constituents that was a marked aspect of the Catholic Revival. James Lidderdale falls afoul of the bishop with a Mass of the Pre-Sanctified and a ceremony of Creeping to the Cross on Good Friday, among other Ritualist practices. His conflict with the bishop brings on a bout of rage and self-pity. He rants that his lack of fealty to his vow of celibacy as a catholic priest has caused this downfall, and he rejects Mark and his mother, and leaves for missionary work in Africa.

In the opening chapters of the book, it is the late 19th century and Mark’s father James, an Anglican priest, has come to St. Simon’s Notting Hill, an outpost of the Catholic Movement in the Church of England. Fr. Lidderdale is given charge of the St. Simon’s Lima Street Mission. The Lima Street Mission typifies the outreach to working class and poor constituents that was a marked aspect of the Catholic Revival. James Lidderdale falls afoul of the bishop with a Mass of the Pre-Sanctified and a ceremony of Creeping to the Cross on Good Friday, among other Ritualist practices. His conflict with the bishop brings on a bout of rage and self-pity. He rants that his lack of fealty to his vow of celibacy as a catholic priest has caused this downfall, and he rejects Mark and his mother, and leaves for missionary work in Africa.

Young Mark and his mother return to Cornwall, and to the care of his benevolent, more protestant, priest-grandfather. Mark is sent to an uncle to be educated in his private, very evangelical boy’s school Haverton House. After a few years Mark runs afoul of his uncle and what Mackenzie calls “his desiccated religion.” On Whit-Sunday (Penetecost: day of the coming of the Holy Spirit) on a walk in the fields, Mark is drawn by church bells to an Anglo-Catholic parish nearby. Mark is swept up in the piety of his childhood by the Sanctus, the Nicene Creed, and the mystery of the mass. He becomes friendly with the vicar, Stephen Ogilvie, and his mother and sisters, and comes into the Ogilvie family’s orbit for the rest of the novel.

Mark is confirmed at Fr. Ogilvie’s church at Meade Cantorum and decides to become a priest. The vicar tutors him in classics and eventually Mark sits for scholarship exams at Oxford. However, in a fit of self-sacrifice he deliberately fails his exams in favor of a less fortunate student. Still set on the priesthood, Mark makes a vow of celibacy and seeks to occupy his time until he can enroll in theological college and qualify for ordination.

In the ensuing year’s Mark lives and works at an Anglo-Catholic mission much like the one his father ran. Here at Chatsea, Mark is tutored by Fr. Rowley, an avid Anglo-Catholic, and selfless missioner to the poor fishing and merchant marine families of the seaside village. Fr. Rowley is widely admired for his work, and by subscription and exhaustive fundraising, he builds a magnificent parish church in Chatsea. However, a new bishop is unwilling to license the church with its Altar of the Dead, where masses are to be offered for the salvation of the souls of the many dead sailors from the community. This flagrantly catholic practice cannot be sanctioned and Fr. Rowley, much like Mark’s own father, abandons his ministry rather than compromise his principles.

Mark decides to be an itinerant preacher, and eventually lands in one of the newly refounded Anglican monasteries. The Order of St. George struggles to pursue its mission when its founder and leading light must constantly travel, preach and fundraise. It is meant to be a mission to sailors, but must close its portside priories and retreat to its mother house to await brighter days. The novices and monks are by turns truly devout and foolishly distracted by the ethereal ceremonies of monastic life and profession. At the end of the novel, Mark leaves the order and rededicates himself to his priestly vocation.

The novel brings to life the conflicts that arose out of Anglo-Catholic revival in Anglicanism as they confronted the movement’s second generation. Mark’s own father and his mentor Fr. Rowley both seek to bring pastoral comfort to their poor communities through Anglo-Catholic liturgy, and catholic theology and piety. Both men are eventually countered by short-sighted, conservative bishops who tout the letter of ecclesial law, and ignore the enormous good that these priests are doing.

The Anglo-Catholic social ministry is foremost in Mackenzie’s view of the movement. The author has great approbation for the devotion these men had to the poor communities that were often the only one’s that would accept their theological and liturgical catholicism. Fr. Rowley’s devotion to his Altar for the Dead, and the deep meaning it held for his parishioners who scrimped and saved to build it, is profound and moving.

Anglo-Catholic monasticism is given less praise as the fictional Order of St. Paul is made to seem at best misguided and unsuccessful, and at worst frivolous. And our hero Mark makes mistakes along his way to spiritual maturity. In an hilarious episode, he attempts to kidnap an evangelical MP’s son and spirit him away to an Anglo-Catholic vicarage where he can be safely converted to the catholic faith and practice. His effort is discovered and thwarted, but we see the sometime overlap and interplay of ecclesial and secular politics.

As the novel concludes, in a nice turnabout, Mark has learned that he is to be ordained, and his first  reflections are on what he will preach the next Sunday -- not on what vestments he’ll wear or rituals he’ll enact. Mackenzie clearly has a high regard for the seriousness of the Catholic Movement, and great sympathy for it. His novel’s chief value for me was its from-the-inside view of the Anglo-Catholic movement. One comes to feel some of the sincerity and piety of the movement’s proponents along with the indignation they feel at evangelicalism efforts to thwart their piety and devotion. The bright line that divided evangelical and Anglo-Catholic practice

reflections are on what he will preach the next Sunday -- not on what vestments he’ll wear or rituals he’ll enact. Mackenzie clearly has a high regard for the seriousness of the Catholic Movement, and great sympathy for it. His novel’s chief value for me was its from-the-inside view of the Anglo-Catholic movement. One comes to feel some of the sincerity and piety of the movement’s proponents along with the indignation they feel at evangelicalism efforts to thwart their piety and devotion. The bright line that divided evangelical and Anglo-Catholic practice

The next two novels in the trilogy are not available online, and are only available from out-of-print book websites for upwards of $100. But I’ve located copies at Columbia’s library, for which I have borrowing privileges. Stay tuned for reviews of The Parson’s Progress and Heaven’s Ladder.

23 March 2008

An Easter Celebration

19 March 2008

My brother and sisters....

This is all of us. In order from the right: me, Kathryn Reinhard, Stephanie Allen, Arianne Weeks, Lindsay Lunnum, Candace Sandfort, Yejide Peters. In the midst of us is Bishop Sisk, flanked by the cathedral deacons. And peeking around Candace's head is Canon Coles. This year's EDNY class of transitional deacons consisted of myself and six women, hence the bishop's form of address to us during our vows: "My brother and sisters..." At rehearsal on Friday, Lindsay turned to me after the first time we heard that particular locution and said, "Well, I guess that's you." Yep, I guess so.

This is all of us. In order from the right: me, Kathryn Reinhard, Stephanie Allen, Arianne Weeks, Lindsay Lunnum, Candace Sandfort, Yejide Peters. In the midst of us is Bishop Sisk, flanked by the cathedral deacons. And peeking around Candace's head is Canon Coles. This year's EDNY class of transitional deacons consisted of myself and six women, hence the bishop's form of address to us during our vows: "My brother and sisters..." At rehearsal on Friday, Lindsay turned to me after the first time we heard that particular locution and said, "Well, I guess that's you." Yep, I guess so. Just before the big event, this is Patience Okwuoha from St. James Fordham Manor, Sibyl Piccone, from Ascension, myself and Tobias S. Haller, BSG, Vicar of St. James. These good folks stood as my presenters for the ordination.

02 March 2008

Sermon for Year A, Lent 4: "Seen and Sent"

Preached on the fourth Sunday of Lent, March 2, 2008 at St. James Episcopal Church Fordham Manor. Scripture readings this sermon is based on can be found here.

A few weeks ago in our Lenten cycle of readings, Abraham set out from Haran to the Land of Canaan. Last week was all about water; Moses brought water from the rock at Meribah and Massah, and Jesus gave the woman at the well living water that would quench her spiritual thirst for ever.

This week, in our readings, we are talking about seeing, about being chosen and sent out to do God’s work in the world. Today we hear a bit about fear, and about faith in God’s plan for our lives and our world.

As our reading today begins, Samuel is pretty downtrodden over King Saul’s failure as the first king of Israel. But God tells Samuel to get over it and to get on the road. God sends Samuel to Bethlehem where he will find Jesse, and his sons, and it is from this relatively unknown and undistinguished family that God has chosen Israel’s next king.

As theologian Rick Marshall points out, Samuel and the Bethlehemites are wary. They are fearful of retaliation by a jealous Saul. This is a kingdom in decline, a fearful people fraught with anxiety. There’s been a failure of leadership, and there is fear about the future.

Samuel takes a heifer to sacrifice at Bethlehem so that Saul won’t suspect anything, and there he asks Jesse and his sons to join in his sacrificial banquet. The first of Jesse’s sons to come before Samuel is Eliab. Samuel immediately thinks, “Oh, this must be him.” Eliab is apparently tall, dark and handsome, just as Saul was. But God tells Samuel no, it is not Eliab.

And then comes one of those scripture passages that ring down the ages, one of those verses that helps us in our own day understand ourselves and God, and what God’s values are, as opposed to our own. First Samuel, chapter 16, verse 7 says, “For the Lord does not see as mortals see; they look on the outward appearance, but the Lord looks on the heart.”

Samuel looks for the most photogenic of Jesse’s sons to be God’s obvious choice. But God is not quite so obvious as that. As all of Jesse’s sons pass before him, God tells Samuel that all of these have been rejected. Samuel has to ask Jesse, “Is this all of them?” That’s when we find out that the youngest, the runt of the litter, is out in the fields tending the sheep. He is sent for, and when this youngest son appears, Samuel notices right away, that he too is handsome, but in a ruddy, hardworking kind of way, not at all like Saul and Eliab.

God tells Samuel, “Rise and anoint him for this is the one.” Samuel

does so, and it is not until just this point in the story, after 13 verses and 7 older brothers, that the scripture finally reveals the identity of this new king. “The Lord came mightily upon David from that day forward.” Ah, yes. David, the fabled king of the united nations of Israel and Judah. This unexpected, youngest son of the obscure Jesse, this shepherd boy, is the one chosen by God to lead the people; he is the one Samuel has been sent to find.

does so, and it is not until just this point in the story, after 13 verses and 7 older brothers, that the scripture finally reveals the identity of this new king. “The Lord came mightily upon David from that day forward.” Ah, yes. David, the fabled king of the united nations of Israel and Judah. This unexpected, youngest son of the obscure Jesse, this shepherd boy, is the one chosen by God to lead the people; he is the one Samuel has been sent to find.Samuel needed to look with the eyes of God on Jesse’s sons before he could really see the one God had chosen. And it is God who has seen David, has looked into his heart. In the very first verse of the reading, God says to Samuel, “I have provided for myself a king” from among the sons of Jesse. The word that we translate as ‘provided’ is actually a form of the verb “ra’ a” meaning literally ‘to see’ in Hebrew. God is telling Samuel that he has seen among Jesse’s sons the one that will become Israel’s legendary yet flawed king.

And this is a beginning of a long, complicated and beautiful love story. The love story of God for David, and of David for his God. You can hear its beginnings in the description of David’s rough beauty. God sees David’s good points and bad. God loves him totally, and God anoints David to do his work in the world. David’s failings do not prevent him from being chosen to lead, and they do not prevent God from loving David unconditionally. And this unconditional love affair will David’s own life and be translated down the generations to David’s eventual heir, Jesus -- and by our baptism into the very body of Christ, unto us.

+++++++++++++++

In our gospel reading, seeing and being sent figure prominently as well. Jesus sends the man born blind to wash in the pool of Siloam which means ‘sent’ and gives him the gift of sight. The man born blind is then able to bear witness to God’s grace in his life, though neither his neighbors, nor the religious authorities thank him for it.

And then there is God’s truth that in some ways justifies all the anxiety. God has a new plan. God is doing a new thing. God is calling new leaders. God is sending his people out to do his work. David -- and then Jesus -- have been chosen, and sent by God to refocus and recreate the relationship between God and humanity. David will serve as proof of God’s unending love for us. And Jesus will prove that God’s love for us extends through the love God bears for the only begotten son. Jesus’ death and resurrection will show the world that God’s plans for us extend beyond the grave, and unto everlasting life.

+++

I think that each of us here this morning can find our own stories in the scriptures we have read this Lent. Many of us like Abraham have journeyed away from our homes -- in search of what might be God’s will for us, God’s plan for our lives. We have traveled from the West Indies and from West Africa, even from West Tennessee. We have, some of us, come like Samuel, seeking new opportunities in places of peace, free from strife and the anxiety of life in unsettled political situations. And we have all found our way to St. James where we bear our own witness to God’s grace in our lives -- and where later this morning at our Annual Meeting we will choose new leaders to guide our parish into the future.

I too was sent to St. James. I came here to learn about parish ministry from Fr. Haller, Br. James, Mr. Green, Ms. Stewart -- from all of you. And soon, I will be sent somewhere else, to shepherd God’s children in another place. Like the man born blind, I have tried to bear witness to God’s grace in preaching from this pulpit and in serving near this altar. Like David, I am the least likely to be called, and yet called I am.

Through my duties here, I have been challenged to make Christ and his redemptive love known. I have learned something about the needs, and concerns of this community and our hopes for the world. I have had the chance to assist in public worship and in the preaching of God’s word, and the ministration of the Sacraments. Each of these is the particular duty of a deacon.

Like Samuel, you have seen me in this new role: at the altar, at the communion rail, in this pulpit -- at coffee hour, in bible study and at parish meetings. And by seeing me in these various roles, you have helped me see myself as a minister to God’s people. You have been minister to me. Yyou have helped me see as God sees. You have helped me to see into my own heart.

This is an anxious time for me. My ordination as a deacon will be two weeks from yesterday, on March 15th at 10:30 in the morning in our Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine. I hope as many of you as can be there will be there. It will be a celebration of your ministry to me as much as an ordination of my ministry.

God is doing a new thing in my life. And yet I am anxious. I haven’t had a good night’s sleep in a couple of weeks now. I’m forgetful of assignments at school and appointments with friends.

Perhaps you know how I feel. You know the anxieties of raising children, working for the best life that you can provide for them. You anoint them with your love, and then let them go to make their own mistakes and triumphs. You know the anxieties of life in our time -- economic fears, fears of violence around the world and here at home. And yet, in the face of these anxieties, we can all be sure of two things. God loves us unconditionally, and God has called each of us. Perhaps it is our sensitivity to the anxieties around us that testifies to the fact that God is calling us to lives of mission, and of service to God and God’s people.

It is clear to me that God has called you to be like Samuel to me, to help me come to understand my duties as a deacon, and one day as a priest. You are called like Samuel to anoint new parish leaders at today’s election. Perhaps some of you will be called as I am to ordained ministry. Someone among you may be the next Barak Obama or Hillary Clinton, chosen like David to lead a great nation. Some of you may be sent, like the man born blind, to bear witness to -- and in fact to administer -- God’s miraculous power to heal.

There is no doubt that there is anxiety in our lives. And there is no doubt that God sees the way forward. And that if we can look into our own hearts and into the hearts of one another, we too will see what God sees. We can come to perceive God’s will for ourselves and for the world. And with God’s grace and with the support of one another, we can do what God calls us to do. We can serve God’s people in whatever ways we are called. We can do justice and love mercy. We can be prophets and priests, and faithful members of the Bishop’s Committee. We can make Christ’s redemptive love known. We can bear witness to the needs, hopes and concerns of our communities and of the world. We can give glory to God in all that we do.

During this Lent, I encourage you all to look within, to see your own role in God’s plan for the salvation of the world, and to take heed of God’s call in your own lives -- and in your own hearts.

Let us pray:

O God, you anointed your servant David to become the shepherd of your people. Prepare our hearts and minds and spirits to do the work you have given us to do. Open our eyes to see within ourselves and others the challenges you call us to, and the gifts you have given us to meet those challenges. Grant us the wisdom to discern your call to us, and the courage to heed it. Amen.

24 February 2008

One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic

Yes, Catholic! And One, and Holy, and Apostolic... These terms are called the 'Four Marks of the Church' and there's a pretty good explanation of their meaning and use on Wikipedia.

and in each of these the term 'catholic' is used to describe the church. In these contexts, catholic is taken to mean 'universal', as it does in the original Greek. By universal, we mean that God's grace through Jesus Christ is available to everyone, everywhere at all times and in all places.

and in each of these the term 'catholic' is used to describe the church. In these contexts, catholic is taken to mean 'universal', as it does in the original Greek. By universal, we mean that God's grace through Jesus Christ is available to everyone, everywhere at all times and in all places.